Ever wonder how fans back home followed an away football game as it was being played back in the day?

Consider that KDKA, the nation’s first radio station, didn’t begin broadcasting from the Westinghouse factory in Pittsburgh until November of 1920, and the first football game broadcast – West Virginia at Pitt – wasn’t until October of 1921. It didn’t take long for the new medium to explode in popularity, but the Rose Bowl wasn’t broadcast nationally until the 1927 game pitting Alabama and Stanford.  Guy with a megaphone.

Guy with a megaphone.

Without a play-by-play, or a knowledgeable sidekick explaining the action on the field, what was a fan to do?

In Eugene, on New Year’s Day in 1917, the solution involved a theater, a Western Union guy, a contraption on a stage and a guy with a megaphone.

***

Heilig Theater, circa 1958. The theater was the Heilig, on Willamette Street between 6th and 7th, a venerable, balconied Vaudeville edifice, later a movie house, eventually among the many victims of urban renewal in the Seventies (the Hult Center occupies its former location).

Heilig Theater, circa 1958. The theater was the Heilig, on Willamette Street between 6th and 7th, a venerable, balconied Vaudeville edifice, later a movie house, eventually among the many victims of urban renewal in the Seventies (the Hult Center occupies its former location).

The Western Union guy was J.A. “Mac” McKevitt, manager of the Eugene  A telegraph operator.Western Union station. McKevitt started work in 1906, when the Western Union office was established, on what is now West Broadway, with one “lady operator” and a part-time messenger boy on his payroll. Starting in around 1915, all road games were reported via Morse code from the remote site to Eugene.

A telegraph operator.Western Union station. McKevitt started work in 1906, when the Western Union office was established, on what is now West Broadway, with one “lady operator” and a part-time messenger boy on his payroll. Starting in around 1915, all road games were reported via Morse code from the remote site to Eugene.

The contraption on the stage was a miniature football field, slightly inclined at  Something like this.the back for ease of visibility to the crowd, made of plywood. Above the field was suspended a small football, connected to a series of pulleys and strings that allowed an operator to move the ball back and forth. Western Union ran a telegraph line from the Broadway station to the Heilig, where McKevitt would set up his portable “ticker” backstage.

Something like this.the back for ease of visibility to the crowd, made of plywood. Above the field was suspended a small football, connected to a series of pulleys and strings that allowed an operator to move the ball back and forth. Western Union ran a telegraph line from the Broadway station to the Heilig, where McKevitt would set up his portable “ticker” backstage.

McKevitt would translate the dots and dashes received from the remote game transmitter into English, relay them to the guy with a megaphone, who would in turn announce the play by play results to the Heilig’s audience, while the boy running the pulleys would move the ball back and forth across the field, and another would track the score on a small scoreboard.

In a 1931 interview, McKevitt said one of his greatest thrills was in the 1917 Tournament of Roses football game, when Oregon defeated Penn by two touchdowns:

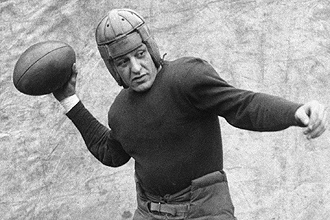

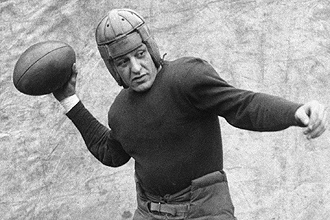

McKevitt took the results of that game play-by-play off the wire and gave them to the announcer at the Heilig theater. The house was packed, Eugene fans were standing in the aisles and clear back to the top of the balcony. The little gridiron was rigged up on stage, and the miniature football was being worked back and forth with the plays. “Mac”  Shy Huntington.remembers getting the message and giving it a word at a time to the announcer: “HUNTINGTON …. MAKES …. TOUCHDOWN!” Pandemonium broke loose, and Mac couldn’t find out whether Oregon converted the [extra] point because the place was so full of noise that he couldn’t hear the ticker, even with his ear down against it. McKevitt was sitting on the stage, with the footlights turned on, and he said as he looked out over the glare of the lights, the theater looked like a giant fountain with hats, coats, sweaters, everything being thrown into the air.”

Shy Huntington.remembers getting the message and giving it a word at a time to the announcer: “HUNTINGTON …. MAKES …. TOUCHDOWN!” Pandemonium broke loose, and Mac couldn’t find out whether Oregon converted the [extra] point because the place was so full of noise that he couldn’t hear the ticker, even with his ear down against it. McKevitt was sitting on the stage, with the footlights turned on, and he said as he looked out over the glare of the lights, the theater looked like a giant fountain with hats, coats, sweaters, everything being thrown into the air.”

— Roy Craft, Eugene Register-Guard, 1931

***

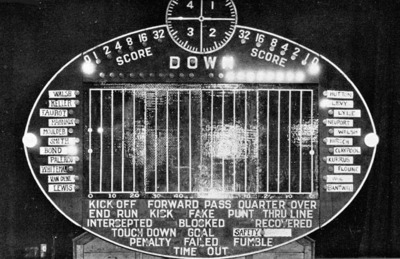

In the mid-1920s, Jack Benefiel, graduate manager of the football team (the equivalent of today’s athletic director), upgraded the “broadcast” technology by purchasing a “grid-graph,” a vertical board equipped with electric lights, that showed the position of the players on the field. But the back end of the system was the same; McKevitt would receive the telegraph updates, communicate them to the grid-graph operator, and the lights would be changed to show the action.

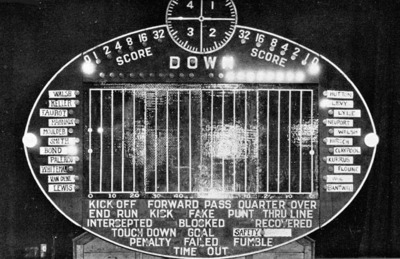

A “grid-graph” from the early 1920s. Note the 7-bit scoring system at the top. Presumably, games would never top 63 points.

A “grid-graph” from the early 1920s. Note the 7-bit scoring system at the top. Presumably, games would never top 63 points.

Of course, the Human Element could occasionally intrude in an event interpreted by grid-graph, with farcical results:

When the Huskers opened their season against the University of Illinois, it was an historical game for several reasons. It was the first Nebraska game to be broadcast on the radio, and the first to be depicted on the Grid-graph. Of even greater importance, it featured the varsity debut of one of the footballs greatest heroes, ‘the Galloping Ghost’, ‘Red’ Grange.

Red GrangeNebraska held its own for most of the game, but ended up losing 24 - 7. The performance of ‘Red’ Grange was too much to overcome. He scored three touchdowns, including a punt return. He showed more brilliant open field running after catching a pass, rambling for 50 yards and the score.

Red GrangeNebraska held its own for most of the game, but ended up losing 24 - 7. The performance of ‘Red’ Grange was too much to overcome. He scored three touchdowns, including a punt return. He showed more brilliant open field running after catching a pass, rambling for 50 yards and the score.

Back in Lincoln, Nebraska, the crowd at the Armory were the only ones to see the most spectacular play of the day. They were the only ones to see the play because it never really happened. The play was the result of confusion by the operators of the Grid-graph and the radio station. The play by play account of the game was being relayed to the Armory by a special wire from Western Union. The same account of the game was being shared by the radio station in its broadcast of the game.

The telegraph operator would type the information, and hand it to the operator of the Grid-graph . When he was done, another man would take the same card and phone the information to the radio station. Occasionally the Grid-graph operator would fall behind, and the dispatches would pile up.

On one occasion, the man relaying the information to the radio station eagerly snatched up the dispatch before the Grid-graph operator had a chance to post the information. The papers that were taken out of sequence contained the record of a touchdown. When it was discovered that a mistake had been made, the Grid-graph operators realized that their score was incorrect. They resolved the situation by showing the crowd a spectacular 70 yard run, by ‘Red’ Grange. A run that never really happened.

— “Watching Away Games Before TV,” Leather Helmets Illustrated

***

By the late 1920s, radio had come to any household that wanted it; all the major college games were broadcast, and the grid-graph technology, along with the theater dates, fell by the wayside (although the concept of packing a house for a transmitted event continued well into the late 20th century, with closed-circuit broadcasts of boxing matches; and of course the modern “sports bar” is essentially performing the same service, sans exclusivity).

Next time another off-the-cuff inanity by Craig James Brock Huard makes you want to throw your remote at the big screen, consider how far we’ve come in 95 years.

Then, go ahead and throw it.

benzduck

benzduck